How does anyone stay sane in this day and age? Between fake news, outrage culture, alternative facts, and the everyday struggle to survive in an economy being subsumed by tech companies, I don’t blame anyone for being a bit uptight. I envy anyone who can step back, see the bigger picture, and retain their sanity.

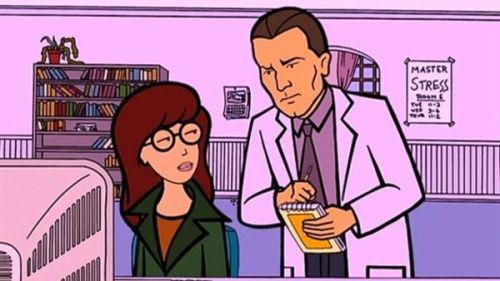

For some, it takes a special kind of strength, perspective, and mental toughness to deal with the totality of the absurdities in this world. Then, there’s Daria Morgendorffer from her remarkably-ahead-of-its-time TV show, “Daria.” When it comes to maintaining a level head while surrounded by the insanities of the modern world, she’s in a league of her own.

I’ve made my love for “Daria” known before. I’ve even shared my excitement on the prospect of a new series. Every time I make the mistake of watching the news for more than two minutes, I find myself wishing I had her nuanced perspective. It’s part of what makes her character so enduring. She’ll see things for what they are, tell it like it is, and offer revealing insights along the way.

Earlier this year, research from Clinical Psychological Science indicated that mental health issues are on the rise among young people. Every day, it seems, a new mental ailment emerges from the evolving media landscape. While mental health issues can be serious, they can also be subject to plenty of absurdities.

As it just so happens, one of my favorite episodes of “Daria” tackled this issue in a way that’s more relevant now than it was back in the early 2000s when it first aired. The title of the episode is called “Psycho Therapy” and the lessons it offers are worth learning.

The synopsis of the episode is fairly basic. Daria’s mother, Helen, is up for a promotion. However, before the law firm she works at can consider her, she and her family are sent to a psychiatric center for personality evaluations. Hilarity ensue, but it’s Daria who ends up making the most astute observations, more so than the doctors on hand.

When Daria and her family first arrive, the staff is most concerned about Daria. Considering how she answered her survey with her trademark sarcasm, that’s understandable. However, when the doctors start to evaluate her and her family, they learn something remarkable.

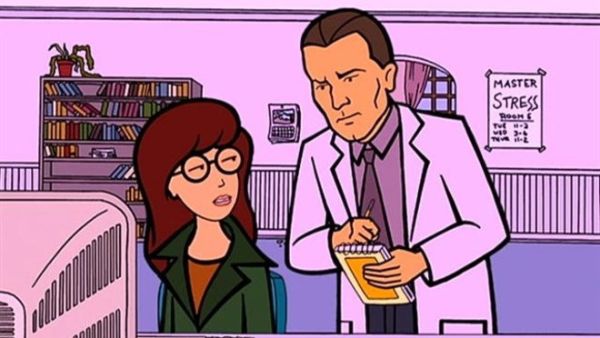

Compared to everyone else in her family, she’s the most mentally stable. Even if you’ve only seen a few episodes of “Daria,” that should be pretty jarring. That’s not to say that she’s the picture of mental health, but according to the doctors in the episode, she’s the most well-adjusted. These are the exact words of Dr. Jean-Michael to Daria.

Dr. Jean-Michael: Daria, I was afraid you had some rather deep-seated problems. But I must say, you’re remarkably well adjusted considering…

Quinn: You’d think someone would’ve invented eye liner before me.

But no, I, Cleopatra, have to come up with all my beauty products on my own.

Oh, what a hard life.

In Quinn’s defense, she was hypnotized when she went on that incoherent ramble. Then again, Quinn Morgandorffer is probably the least defensive character in the show and would probably benefit from a healthy bit of therapy.

What makes this assessment more revealing is just how much Daria is surrounded by intense personalities, so to speak. I won’t go so far as to say these personalities are on par with mental illness, but they certainly walk the line. While that’s part of what makes these characters interesting, it also highlights an important concept that Daria Morgandorffer embodies.

At her core, Daria is a hardcore realist. She’s not a nihilist, a social constructionist, or an existentialist. She’s someone who sees both the surface and the forces just below that surface. From there, she makes a cold, calculated assessment that is devoid of needless emotional breadth, unless you count the sarcasm.

This is how she’s able to effectively break down the mental quirks of her parents, Jake and Helen Morgandorffer. Throughout the series, their relationship goes through a lot of atypical stresses. Just check out Season 3, Episode 10, entitled “Speedtrapped” for a clear depiction of those stresses.

On top of that, they both have some fairly eccentric personality quirks. Her mother is an incredibly high-strung, career-obsessed woman who constantly worries about how “normal” both her daughters are. Her father is an overly-dense, exceedingly histrionic man who always seems like he’s in the middle of a mid-life crisis.

Even a professional would have trouble making sense of their mental state. Daria does it in just a few short sentences.

Daria: Mom’s resentful that she has to work so hard, which obscures her guilt about actually wanting to work so hard. Dad’s guilty about being less driven than Mom, but thinks it’s wrong to feel that way. So, he hides behind a smokescreen of cluelessness.

Behind the heavy monotone and light sarcasm, this shows that Daria knows her parents. Given how they behave throughout the episode, she demonstrates that she actually knows them better than they know themselves. There’s even a scene towards the end of the episode where they try to mimic one another. It ends up getting pretty dramatic for everyone, except for Daria.

Helen: I mean Dammit! I lost another client! I can’t understand why! Dammit! Nobody likes poor old Jake. Should I think about the reason? Oh, must be my father’s fault. Where’s the newspaper, dammit!

Jake: Let me bring home the pizza. I have to be the one doing everything so everyone will thank me and tell me what a big superwoman I am. I’m very, very important and very, very stressed and I don’t have time to actually do anything for anyone else, but I can pretend I care, can’t I?

This is some pretty brutal honesty, even by “Daria” standards. They reveal some pretty unhealthy sentiments that probably need more than just advice and therapy. They reflect many of the quirks and side-plots that Daria’s parents experience throughout the show with Helen constantly obsessing over her career and Jake obsessing over whatever is stressing him out at the moment.

Daria’s ability to sift through all that and make a clear, honest assessment is both remarkable and refreshing. Even though these are her parents, she doesn’t pull any punches. Moreover, she doesn’t make any value judgments either. She doesn’t take sides or show scorn. She’s just tells it like it is. She says what the audience feels and does it in that lovable, monotone sort of way.

Her being able to make that assessment is profound. Doing so while maintaining mental stability is just as amazing. The fact she can maintain this perspective around personalities that range from ditzy cheerleader types like Brittney Taylor and touchy-feely teachers like Timothy O’Neill show why Daria is the emotional anchor of the show.

Back in the early 2000s, Daria’s knack for being level-headed while surrounded by so many bizarre characters made for great entertainment. Today, it acts as a radical departure from how we make sense of a world where every news clip, viral video, and hashtag is measured by the emotional outburst it triggers.

What Daria does in “Psycho Therapy” is something that has become far less common with each passing year. She makes a clear, concise assessment of other peoples’ behaviors and attitudes without casting judgement. She doesn’t whine about other peoples’ shortcomings or bemoan misguided efforts to treat them. She just points out the cold, hard facts and lets them stand on their own merit.

Contrast that with how every comment about someone, whether it’s in person or online, is laced with value judgments. You say you like video games and immediately, you’re judged as this angry fanboy who rages whenever someone dares to significantly change a particular aspect of your game. You say you’re a feminist and immediately, you’re judged as a man-hating bitch who blames men for every single ill on the planet.

It’s not enough to just have an opinion. It’s not even enough to have personal likes or dislikes. Everything you do and why you do it has to be an indictment on your politics, your identity, and the society around you. That’s not just misguided and judgmental. It’s mentally exhausting.

Being constantly judged, online and offline, every hour of every day is sure to be stressful. It’s no wonder why it seems as though more young people are development mental health issues. Daria may seem like the most unhappy person in her show, but compared to what some people deal with in the real world, she’s a picture of sanity.

At the end of the episode, it’s not Daria’s choices that lead to the resolution. All she does is provide commentary. It’s Helen and Jake, her emotionally convoluted parents, who chart their own path. That kind of lesson wasn’t as necessary in June 2000 when this episode first aired, but it’s one worth re-learning today.